The theory of primary mental abilities. Psychological theories of intelligence. Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence. Cubic model of the structure of intelligence (J. Gilford). Robert Sternberg. Three-component theory of intelligence

Last update: 31/08/2014

Intelligence is one of the most discussed phenomena in psychology, but despite this, there is no standard definition of what exactly can be considered "intelligence". Some researchers believe that intelligence is an ability, while others are closer to the hypothesis that intelligence includes a number of abilities, skills and talents.

Over the past 100 years, many theories of intelligence have emerged, some of which we will consider today.

Theory of Charles Spearman. General intelligence

British psychologist Charles Spearman (1863-1945) described a concept he called general intelligence, or the g factor. Using a technique known as factor analysis, Spearman ran a series of intelligence tests and concluded that the scores on those tests were surprisingly similar. People who do well on one test tend to do well on others. And those who scored low on one test, as a rule, received poor marks on the rest. He concluded that intelligence is a general cognitive ability that can be measured and expressed numerically.

Louis L. Thurstone. Primary Mental Ability

Psychologist Louis L. Thurstone (1887-1955) proposed a different theory of intelligence from the previous one. Instead of viewing intelligence as a single, general faculty, Thurstone's theory includes seven "primary mental faculties". Among the primary abilities he described are:

- verbal understanding;

- inductive reasoning;

- fluency of speech;

- perceptual speed;

- associative memory;

- computing ability;

- spatial visualization.

Howard Gardner. Multiple intelligence

One of the latest and most interesting theories is the theory of multiple intelligences developed by Howard Gardner. Instead of focusing on the analysis of test scores, Gardner stated that the numerical expression of human intelligence is not complete and does not accurately describe a person's abilities. His theory describes eight distinct intelligences based on skills and abilities that are valued across cultures:

- visual-spatial intelligence;

- verbal-linguistic intelligence;

- bodily-kinesthetic intelligence

- logical-mathematical intelligence

- interpersonal intelligence;

- intrapersonal intelligence;

- musical intelligence;

- naturalistic intelligence.

Robert Sternberg. Three-component theory of intelligence

Psychologist Robert Sternberg defined intelligence as "the mental activity of selecting, shaping, and adapting to the real conditions of one's life." He agrees with Gardner that intelligence is much broader than one ability, but suggested that some of Gardner's intelligences be treated as separate talents.

Sternberg proposed the idea of what he called "successful intelligence". Its concept consists of three factors:

- Analytical mind. This component refers to the ability to solve problems.

- Creative intelligence. This aspect of intelligence is based on the ability to deal with new situations using past experience and current skills.

- Practical intelligence. This element refers to the ability to adapt to environmental changes.

None of the psychologists has yet been able to formulate the final concept of intelligence. They acknowledge that this debate about the exact nature of this phenomenon is still ongoing.

The four theories of intelligence discussed in this section differ in several respects.

Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences See → Gardner attempts to explain the wide variety of adult roles found in different cultures. He believes that such diversity cannot be explained by the existence of a basic universal intellectual ability, and suggests that there are at least seven different manifestations of intelligence, present in various combinations in each individual. According to Gardner, intelligence is the ability to solve problems or create products that have value in a particular culture. According to this view, a Polynesian navigator with developed skills in navigating the stars, a figure skater who successfully performs a triple “Axel”, or a charismatic leader who draws crowds of followers along with him are no less “intellectual” than a scientist, mathematician or engineer.

Anderson's Theory of Intelligence and Cognitive Development See → Anderson's theory attempts to explain various aspects of intelligence - not only individual differences, but also the growth of cognitive abilities in the course of individual development, as well as the existence of specific abilities, or universal abilities that do not differ from one individual to another, such as the ability to see objects in three dimensions. To explain these aspects of intelligence, Anderson suggests the existence of a basic processing mechanism equivalent to Spearman's general intelligence, or q factor, along with specific processors responsible for propositional thinking and visual and spatial functioning. The existence of universal abilities is explained using the concept of "modules", the functioning of which is determined by the degree of maturation.

Sternberg's triarchic theory See → Sternberg's triarchic theory is based on the view that earlier theories of intelligence are not wrong, but only incomplete. This theory consists of three sub-theories: a component sub-theory that considers the mechanisms of information processing; experimental (experiential) sub-theory, which takes into account individual experience in solving problems or being in certain situations; contextual sub-theory that considers the relationship between the external environment and individual intelligence.

Bioecological theory of Cesi See → Cesi's bioecological theory is a development of Sternberg's theory and explores the role of context at a deeper level. Rejecting the idea of a single general intellectual ability to solve abstract problems, Cesi believes that the basis of intelligence is multiple cognitive potentials. These potentials are biologically determined, but the degree of their manifestation is determined by the knowledge accumulated by the individual in a certain area. Thus, according to Cesi, knowledge is one of the most important factors of intelligence.

Despite these differences, all theories of intelligence have a number of common features. All of them try to take into account the biological basis of intelligence, whether it be a basic processing mechanism or a set of multiple intellectual abilities, modules or cognitive potentials. In addition, three of these theories emphasize the role of the context in which the individual functions, that is, environmental factors that influence intelligence. Thus, the development of a theory of intelligence suggests further study of the complex interactions between biological and environmental factors that are at the center of modern psychological research.

How accurately do intelligence tests reflect intelligence?

SAT and GRE test scores - accurate indicators of intelligence

Why IQ, SAT and GRE don't measure general intelligence

Thousands of "validity" studies show that general intelligence tests predict a wide range of different behaviors, although not perfectly, better than any other method known to us. Grades of first-year students are predicted somewhat better by IQ scores than by grades or characteristics obtained by first-year students. high school. Grades obtained by students in their first year of graduate school are also better predicted by IQ scores than university grades and characteristics. But the accuracy of prediction based on IQ (or SAT or GRE) is limited, and scores for many candidates will not be as expected. The test makers argue that even limited predictability can help enrollment officials educational establishments, make a better decision than without the use of tests (Hunt, 1995). See →

GDP. Chapter 13

In this chapter, we will consider three theoretical approaches to personality that have dominated the history of personality psychology throughout the 20th century: psychoanalytic, behavioral, and phenomenological approaches.

Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence. The first work in which an attempt was made to analyze the structure of the properties of intelligence appeared in 1904. Its author, Charles Spearman, an English statistician and psychologist, the creator of factor analysis, drew attention to the fact that there are correlations between different intelligence tests: the one who is good performs some tests is, on average, quite successful in others. In order to understand the reason for these correlations, Spirzan developed a special statistical procedure that allows you to combine correlated intelligence measures and determine what minimal amount intellectual characteristics, which is necessary in order to explain the relationships between different tests. This procedure was, as we have already mentioned, called factor analysis, various modifications of which are actively used in modern psychology.

After factoring different tests of intelligence, Spearman came to the conclusion that correlations between tests are the result of a common factor underlying them. He called this factor the "g factor" (from the word general - general). The general factor is crucial for the level of intelligence: according to Spearman's ideas, people differ mainly in the degree to which they possess the g factor.

In addition to the general factor, there are also specific ones that determine the success of various specific tests. So, the performance of spatial tests depends on the factor g and spatial abilities, mathematical tests - on the factor g and mathematical abilities. The greater the influence of the g factor, the higher the correlations between tests; the greater the influence of specific factors, the less the relationship between the tests. The influence of specific factors on individual differences between people, according to Spearman, is of limited importance, since they do not appear in all situations, and therefore they should not be guided by when creating intelligence tests.

Thus, the structure of intellectual properties proposed by Spearman turns out to be extremely simple and is described by two types of factors - general and specific. These two types of factors gave the name of Spearman's theory - the two-factor theory of intelligence.

In a later revision of this theory, which appeared in the mid-1920s, Spearman acknowledged the existence of links between certain intelligence tests. These connections could not be explained

neither the factor g nor specific abilities, and therefore Spearman introduced to explain these relationships, the so-called group factors - more general than specific, and less general than the factor g. However, the main postulate of Spearman's theory remained unchanged: individual differences between people in terms of intellectual characteristics are determined mainly by common abilities, i.e. factor g.

But it is not enough to single out the factor mathematically: it is also necessary to try to understand its psychological meaning. To explain the content of the common factor, Spearman made two assumptions. Firstly, the factor g determines the level of "mental energy" necessary for solving various intellectual problems. This level is not the same for different people, which leads to differences in intelligence. Secondly, the factor g is associated with three features of consciousness - with the ability to assimilate information (acquire new experience), the ability to understand the relationship between objects and the ability to transfer existing experience to new situations.

Spearman's first suggestion, regarding the level of energy, is difficult to see as anything other than a metaphor. The second assumption turns out to be more specific, determines the direction of the search for psychological characteristics and can be used to decide what characteristics are essential for understanding individual differences in intelligence. These characteristics should, firstly, be correlated with each other (since they should measure general abilities, i.e. the factor g); secondly, they can be addressed to the knowledge that a person has (since a person’s knowledge indicates his ability to assimilate information); thirdly, they must be related to the decision logical tasks(understanding different ratios between objects) and, fourthly, they must be associated with the ability to use existing experience in an unfamiliar situation.

Test tasks related to the search for analogies turned out to be the most adequate for identifying such psychological characteristics. An example of a technique based on the search for analogies is the Raven test (or Raven Progressive Matrices), which was created specifically for the diagnosis of the g factor. One of the tasks of this test is shown in Figure 10.

The ideology of Spearman's two-factor theory of intelligence was used to create a number of intelligence tests, in particular, the Wechsler test, which is currently used. However, since the end of the 1920s, works have appeared in which doubts have been expressed about the universality of the factor g for understanding individual differences in intellectual characteristics, and at the end of the 30s, the existence of mutually independent factors of intelligence was experimentally proved.78

Rice. 10. An example of a task from Raven's text

Primary mental abilities. In 1938, Lewis Thurston's work "Primary Mental Powers" was published, in which the author introduced the factorization of 56 psychological tests diagnosing different intellectual characteristics. Based on this factorization, Thurston identified 12 independent factors. The tests that were included in each factor were taken as the basis for creating new test batteries, which in turn were carried out on different groups of subjects and again factorized. As a result, Thurston came to the conclusion that there are at least 7 independent intellectual factors in the intellectual sphere. The names of these factors and the interpretation of their content are presented in Table 9.

Letter designation and name of the factor

Verbal understanding

fluency

Operations with numbers

Spatial characteristics

The ability to perceive

spatial

ratios

Ability to remember verbal stimuli

The ability to quickly notice similarities and differences in stimulus objects

The ability to find general rules in the structure of the analyzed material

table 9

Diagnostic methods

Dictionary texts (understanding of words, selection of synonyms and antonyms) Verbal analogies Completion of sentences

Selection of words for

certain

criteria (eg.

beginning

with a certain letter)

Anogram solution

Selection of rhymes

The speed of solving arithmetic problems

Rotation tests in 2D and 3D

Pair association test

Tests for comparing different objects Reading mirror reflection of text

Analogies

Continuation of digital and alphabetic sequences

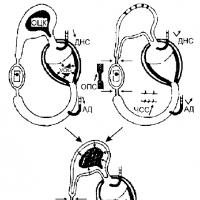

cubic model structures of the intellect. The largest number of characteristics underlying individual differences in the intellectual sphere was named by J. Gilford. According to Guilford's theoretical ideas, the performance of any intellectual task depends on three components - operations, content and results.

Operations are those skills that a person must show when solving an intellectual problem. He may be required to understand the information that is presented to him, memorize it, search for the correct answer (convergent products), find not one, but many answers that equally correspond to the information he has (divergent products), and evaluate the situation in terms of right or wrong. , good bad.

The content is determined by the form of information submission. Information can be presented in visual form and in auditory form, it can contain symbolic material, semantic (i.e. presented in verbal form) and behavioral (i.e., detected when communicating with other people, when it is necessary to understand from the behavior of other people how respond appropriately to the actions of others).

Results - what a person who solves an intellectual problem eventually comes to can be presented in the form of single answers, in the form of classes or groups of answers. Solving a problem, a person can also find a relationship between different objects or understand their structure (the system underlying them). He can also transform the end result of his intellectual activity and express it in a completely different form than that in which the source material was given. Finally, he can go beyond the information given to him in the test material and find the meaning or hidden meaning underlying this information, which will lead him to the correct answer.

The combination of these three components of intellectual activity - operations, content and results - forms 150 characteristics of intelligence (5 types of operations multiplied by 5 forms of content and multiplied by 6 types of results, i.e. 5x5x6=150). For clarity, Guilford presented his model of the structure of intelligence in the form of a cube, which gave the name to the model itself. Each face in this cube is one of three components, and the whole cube consists of 150 small cubes corresponding to different intellectual characteristics (see fig. P.)

For each cube (each intellectual characteristic), according to Guilford, tests can be created that will allow

6 M. Egorova 8

Operations Understanding Memory

Operations Understanding Memory

Convergent products Divergent products Estimation Fig. eleven. Guilford's model of the structure of intelligence

diagnose this feature. For example, solving verbal analogies requires understanding the verbal (semantic) material and establishing logical connections (relationships) between objects. Determining what is incorrectly depicted in the picture (Fig. 12) requires a systematic analysis of the material presented in visual form and its evaluation.

Conducting almost 40 years of factor-analytical research, Guilford created tests for diagnosing two-thirds of the theoretically defined intellectual characteristics and showed that at least 105 independent factors can be distinguished (Guilford J.P., 1982). However, the mutual independence of these factors is constantly questioned, and the very idea of Guilford about the existence of 150 separate,

Rice. 12. An example of one of the Guilford tests

IQs that are not related to each other does not meet with sympathy from psychologists who study individual differences: they agree that the whole variety of intellectual characteristics cannot be reduced to one common factor, but compiling a catalog of one and a half hundred factors is the other extreme. It was necessary to look for ways that would help to streamline and correlate with each other the various characteristics of intelligence.

The opportunity to do this was seen by many researchers in finding such intellectual characteristics that would represent an intermediate level between the general factor (factor g) and individual adjacent characteristics (such as those identified by Thurston and Gilford).

Hierarchical models of intelligence. By the beginning of the 1950s, works appeared in which it is proposed to consider various intellectual characteristics as hierarchically organized structures.

In 1949, the English researcher Cyril Burt published a theoretical scheme according to which there are 5 levels in the structure of intelligence. The lowest level is formed by elementary sensory and motor processes. A more general (second) level is perception and motor coordination. The third level is represented by the processes of developing skills and memory. An even more general level (fourth) is the processes associated with logical generalization. Finally, the fifth level forms the general intelligence factor (g). Burt's scheme practically did not receive experimental verification, but it was the first attempt to create a hierarchical structure of intellectual characteristics.

The work of another English researcher, Philip Vernon, which appeared at the same time (1950), was confirmed by factor-analytic studies. Vernon identified four levels in the structure of intellectual characteristics - general intelligence,

|

major group factors, minor group factors and] specific factors (see Figure 13).

General intelligence, according to Vernon's scheme, is divided into two "factors. One of them is associated with verbal and mathematical abilities and depends on education. The second is less influenced by education and relates to spatial and technical abilities and practical skills. These factors, in in turn, are subdivided into less general characteristics similar to Thurston's primary mental abilities, and the least general level is formed by features associated with the performance of specific tests.

The most famous in modern psychology hierarchical structure of the intellect was proposed by the American researcher Raymond Cattell (Cattell R., 1957, 1971). Cattell and his colleagues suggested that] certain intellectual characteristics identified on the basis of factor analysis (such as primary mental abilities

Thurston or independent Guildford factors) under secondary factorization will be combined into two groups or, in the terminology of the authors, into two broad factors. One of them, called crystallized intelligence, is associated with the knowledge and skills that a person has acquired - "crystallized" in the learning process. The second broad factor - fluid intelligence - is less related to learning and more to the ability to adapt to unfamiliar situations. The higher the fluid intelligence, the easier a person copes with new, unusual problem situations for him.

Initially, it was assumed that fluid intelligence is more connected with the natural inclinations of the intellect and is relatively free from the influence of education and upbringing (its diagnostic tests were called so - culture-free tests). Over time, it became clear that both secondary factors, although to varying degrees, are nevertheless associated with education and are equally influenced by heredity (Horn J., 1988). At present, the interpretation of fluid and crystallized intelligence as characteristics of different nature is no longer used (one is more “social”, and the other is more “biological”).

An experimental verification of the assumption of the authors about the existence of these factors, more general than primary abilities, but less general than the g factor, was confirmed. Both crystallized and fluid intelligence turned out to be fairly general characteristics of intelligence that determine individual differences in the performance of a wide range of intelligence tests. Thus, the structure of intelligence proposed by Cattell is a three-level hierarchy. The first level is the primary mental faculties, the second level is the broad factors (fluid and crystallized intelligence) and the third level is the general intelligence.

Subsequently, with continued research by Cattell and his colleagues, it was found that the number of secondary, broad factors, is not reduced to two. There are grounds, besides fluid and crystallized intelligence, for singling out 6 more secondary factors. They combine a smaller number of primary mental faculties than fluid and crystallized intellect, but are nevertheless more general than primary mental faculties. These factors include the ability to process visual information, the ability to process acoustic information, short-term memory, long-term memory, mathematical ability and speed of execution of intellectual tests.

Summing up the works that proposed hierarchical structures of intelligence, we can say that their authors sought to reduce the number of specific intellectual characteristics that

constantly appear in the study of the intellectual sphere. They tried to identify secondary factors that are less general than the g factor, but more general than the various intellectual characteristics related to the level of primary mental abilities. The proposed methods for studying individual differences in the intellectual sphere are test batteries that diagnose the psychological characteristics described by precisely these secondary factors.

2. COGNITIVE THEORIES OF INTELLIGENCE

Cognitive theories of intelligence suggest that the level of human intelligence is determined by the efficiency and speed of information processing processes. According to cognitive theories, the speed of information processing determines the level of intelligence: the faster information is processed, the faster the test task is solved and the higher the level of intelligence is. As indicators of the information processing process (as components of this process), any characteristics that can indirectly indicate this process can be selected - reaction time, brain rhythms, various physiological responses. As a rule, various speed characteristics are used as the main components of intellectual activity in studies conducted in the context of cognitive theories.

As already mentioned when discussing the history of the psychology of individual differences, the speed of performing simple sensorimotor tasks was used as an indicator of intelligence by the creators of the first tests of mental abilities - Galton and his students and followers. However, their proposed methodological techniques poorly differentiated subjects, were not associated with vital indicators of success (such as academic performance), and were not widely used.

The revival of the idea of measuring intelligence using varieties of reaction time is associated with interest in the components of intellectual activity and, looking ahead, we can say that the result of modern verification of this idea differs little from the one that

got Galton.

To date, this direction has significant experimental data. Thus, it has been established that intelligence correlates weakly with the time of a simple reaction (the highest correlations rarely exceed -0.2, and in many studies they are generally close to 0). Over time, correlation choice responses are somewhat

higher (on average, up to -0.4), and the greater the number of stimuli from which one must be selected, the higher is the connection between reaction time and intelligence. However, in this case, in a number of experiments, the relationship between intelligence and reaction time was not found at all.

Relationships of intelligence with recognition time often turn out to be high (up to -0.9). However, data on the relationship between recognition time and intelligence were obtained from small samples. According to Vernon P.A., 1981, average value the sample in these studies by the beginning of the 80s was 18 people, and the maximum was 48. In a number of works, the samples included mentally retarded subjects, which increased the spread in intelligence scores, but at the same time, due to the small sample size, it overestimated the correlations. In addition, there are works in which this connection was not obtained: correlations between the recognition time and intelligence vary in different works from -0.82 (the higher the intelligence, the shorter the recognition time) to 0.12 (Lubin M., FernenderS ., 1986).

Less inconsistent results were obtained when determining the execution time of complex intellectual tests. So, for example, in the works of I. Hunt, the assumption that the level of verbal intelligence is determined by the speed of retrieval of information stored in long-term memory was tested (Hunt E., 1980). Hunt recorded the time of recognition of simple verbal stimuli, for example, the rate of assigning the letters "A" and "a" to the same class, since it is the same letter, and the letters "A" and "B" - to different classes. Correlations of recognition time with verbal intelligence diagnosed by psychometric methods were equal to -0.30 - the shorter the recognition time, the higher the intelligence.

Thus, as can be seen from the magnitude of the correlation coefficients obtained between speed characteristics and intelligence, different reaction time parameters rarely show reliable relationships with intelligence, and if they do, these relationships turn out to be very weak. In other words, speed parameters cannot in any way be used to diagnose intelligence, and only a small part of individual differences in intellectual activity can be explained by the influence of information processing speed.

But the components of intellectual activity are not limited to speed correlates of mental activity. An example of a qualitative analysis of intellectual activity is the component theory of intelligence, which will be discussed in the next section.

In component intelligence Sternberg identifies three types of processes or components (Sternberg R., 1985). Performing components are the processes of perceiving information, storing it in short-term memory and retrieving information from long-term memory; they are also related to counting and comparing objects. The components associated with the acquisition of knowledge determine the processes of obtaining new information and its preservation. Metacompo-! nents control performance components and knowledge acquisition; they also define strategies for solving problem situations. As Sternberg's studies have shown, the success of solving intellectual problems depends, first of all, on the adequacy of the components used, and not on the speed of information processing. Often a more successful solution is associated with more time.

empiric intelligence includes two characteristics - the ability to cope with a new situation and the ability to automate some processes. If a person is faced with a new problem, the success of its solution depends on how quickly and effectively the metacomponents of activity responsible for developing a strategy for solving the problem are updated. In cases where problems X is not new for a person, when he encounters it not for the first time, the success of its solution is determined by the degree of automation of skills.

situational intelligence- this is the intelligence that manifests itself in everyday life when solving everyday problems (practical intelligence) and when communicating with others (social intelligence).

To diagnose component and empirical intelligence, Sternberg uses standard intelligence tests, i.e. The theory of triune intelligence does not introduce completely new indicators for defining two types of intelligence, but provides a new explanation for the indicators used in psychometric theories.

Since situational intelligence is not measured in psychometric theories, Sternberg developed his own tests to diagnose it. They are based on the resolution of various practical situations and turned out to be quite successful. The success of their implementation, for example, significantly correlates with the level wages, i.e. with an indicator indicating the ability to resolve real life problems.

Hierarchy of intellects. The English psychologist Hans Eysenck distinguishes the following hierarchy of intelligence types: biological-psychometric-social.

Based on data on the associations of speed characteristics with intelligence measures (which, as we have seen, are not very reliable), Eysenck believes that much of the phenomenology of intelligence testing can be interpreted in terms of temporal characteristics - the speed of solving intelligence tests is considered by Eysenck to be the main reason for individual differences in intelligence points obtained during the testing procedure. The speed and success of performing simple tasks is considered in this case as the probability of the unhindered passage of encoded information through the "channels of the nervous connection" (or, conversely, the probability of delays and distortions that occur in the conducting nerve pathways). This probability is the basis of "biological" intelligence.

Biological intelligence, measured by reaction time and psychophysiological measures, and determined, as Eysenck (1986) suggests, by genotype and biochemical and physiological patterns, determines to a large extent "psychometric" intelligence, that is, the one that we measure with IQ tests, but IQ (or psychometric intelligence) tests

there is the influence of not only biological intelligence, but also cultural factors - the socio-economic status of the individual, his education; niya, the conditions in which he was brought up, etc. Thus, there is reason to distinguish not only psychometric and biological, but; and social intelligence.

The IQs used by Eysenck are standard procedures for evaluating reaction time, psychophysiological measures related to the diagnosis of brain rhythm, and psychometric measures of intelligence. Eysenck does not propose any new characteristics for the definition of social intelligence, since the goals of his research are limited to the diagnosis of biological intelligence.

The theory of many intelligences. Howard Gardner's theory, like the Sternberg and Eysenck theories described here, uses a broader view of intelligence than that offered by psychometric and cognitive theories. Gardner believes that there is no single intelligence, but there are at least 6 separate intelligences. Three of them describe traditional theories of intelligence - linguistic, logico-mathematical And spatial. The other three, although they may seem at first glance strange and not related to the intellectual field, deserve, according to Gardner, the same status as traditional intelligences. These include musical intelligence, kinesthetic intelligence And personal intelligence(Gardner H., 1983).

Musical intelligence is related to rhythm and ear, which are the basis of musical ability. Kinesthetic intelligence is defined as the ability to control one's body. Personal intelligence is divided into two - intrapersonal and interpersonal. The first of them is associated with the ability to manage one's feelings and emotions, the second - with the ability to understand other people and predict their actions.

Using traditional intelligence testing, data on various brain pathologies, and cross-cultural analysis, Gardner came to the conclusion that the intelligences he identified are relatively independent of each other.

Gardner believes that the main argument for attributing musical, kinesthetic and personal characteristics specifically to the intellectual sphere is that these characteristics, to a greater extent than traditional intelligence, determined human behavior from the moment of the dawn of civilization, were more valued at the dawn human history and still in some cultures determine the status of a person to a greater extent than, for example, logical thinking.

Gardner's theory caused a great deal of discussion. It cannot be said that his arguments convinced that the intellectual sphere makes sense.

interpret as broadly as he does. However, the very idea of studying intelligence in a broader context is currently considered very promising: it is associated with the possibility of increasing the reliability of long-term predictions.

CONCLUSIONS

The history of the search and selection of characteristics that most clearly demonstrate the differences between people in the intellectual sphere is a constant, the emergence of more and more new characteristics associated with intellectual activity. Attempts to reduce them to a more or less observable number of intellectual parameters have proved to be the most effective in the psychometric tradition of intelligence research. Using factor-analytical techniques and focusing mainly on secondary factors, researchers identify the main intellectual parameters, the number of which does not exceed one dozen and which are decisive for individual differences in a variety of intellectual characteristics.

Studies of the structure of intelligence, carried out in cognitive theory, are associated with the search for correlates of intellectual activity and, as a rule, highlight the speed parameters for solving relatively simple problem situations. Data on the relationship of speed characteristics with intelligence indicators are currently quite contradictory and can only explain a small proportion of individual differences.

Intelligence research conducted in the last decade is not directly related to the search for new intellectual parameters. Their goal is to expand ideas about the intellectual sphere and include non-traditional ideas for the study of intelligence. In particular, in addition to the usual psychometric indicators of intelligence, all theories of multiple intelligence also consider social intelligence, i.e. the ability to effectively resolve real life problems.

CHAPTER 5 TEMPERAMENT AND PERSONALITY

None psychological features do not have such a long history of their study as temperament. When analyzing typological approaches to the study of individual differences, the main stages of this history were described. This chapter will tell you what new modern works have brought to the study of temperament - what are the modern ideas about temperament, and what features of temperament stand out in today's psychology of individual differences as the most important for understanding it.

The analysis of the features of the personality sphere presented in this chapter is limited to the material obtained in the context of the theory of traits, i.e., the results of only those studies of personality that were carried out directly in the framework of the study of individual differences will be described here.

1. STRUCTURE OF TEMPERAMENT PROPERTIES

Until the 1960s, intelligence research was dominated by the factorial approach. However, with the development of cognitive psychology, with its emphasis on information processing models (see Chapter 9), a new approach has emerged. Different researchers define it somewhat differently, but the main idea is to explain intelligence in terms of the cognitive processes that occur when we perform intellectual activities (Hunt, 1990; Carpenter, Just & Shell, 1990). The information approach raises the following questions:

1. What mental processes are involved in various intelligence tests?

2. How fast and accurate are these processes?

3. What kind of mental representations of information are used in these processes?

Instead of explaining intelligence in terms of factors, the informational approach seeks to determine what mental processes are behind intelligent behavior. He assumes that individual differences in the solution of a particular problem depend on the specific processes involved in its solution by different individuals, and on the speed and accuracy of these processes. The goal is to use the information model of a particular task to find measures that characterize the processes involved in this task. These measures can be very simple, such as the response time to multiple choices, or the reaction rate of the subject, or the eye movements and cortical evoked potentials associated with that response. Any information necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of each component process is used.

Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences

Howard Gardner (Gardner, 1983) developed his theory of multiple intelligences as a radical alternative to what he calls the "classical" view of intelligence as the capacity for logical reasoning.

Gardner was struck by the variety of adult roles in different cultures - roles based on a wide variety of abilities and skills, equally necessary for survival in their respective cultures. Based on his observations, he came to the conclusion that instead of a single basic intellectual ability, or "g factor", there are many different intellectual abilities that occur in various combinations. Gardner defines intelligence as "the ability to solve problems or create products, due to specific cultural characteristics or social environment" (1993, p. 15). It is the multiple nature of intelligence that allows people to take on roles as varied as doctor, farmer, shaman, and dancer (Gardner, 1993a).

Gardner notes that intelligence is not a “thing”, not a device located in the head, but “a potential, the presence of which allows an individual to use forms of thinking that are adequate to specific types of context” (Kornhaber & Gardner, 1991, p. 155). He believes that there are at least 6 different types of intelligence that do not depend on each other and act in the brain as independent systems (or modules), each according to its own rules. These include: a) linguistic; b) logical and mathematical; c) spatial; d) musical; e) bodily-kinesthetic and f) personality modules. The first three modules are familiar components of intelligence, and they are measured by standard intelligence tests. The last three, according to Gardner, deserve a similar status, but Western society has emphasized the first three types and virtually excluded the rest. These types of intelligence are described in more detail in Table. 12.6.

Table 12.6. Seven intellectual abilities according to Gardner

1. Verbal intelligence- the ability to generate speech, including the mechanisms responsible for the phonetic (speech sounds), syntactic (grammar), semantic (meaning) and pragmatic components of speech (the use of speech in various situations).

2. Musical intelligence - the ability to generate, transmit and understand the meanings associated with sounds, including the mechanisms responsible for the perception of pitch, rhythm and timbre (qualitative characteristics) of sound.

3. Logico-mathematical intelligence - the ability to use and evaluate the relationship between actions or objects when they are not actually present, that is, to abstract thinking.

4. Spatial intelligence - the ability to perceive visual and spatial information, modify it and recreate visual images without recourse to the original stimuli. Includes the ability to construct images in three dimensions, as well as mentally move and rotate these images.

5. Body-kinesthetic intelligence - the ability to use all parts of the body when solving problems or creating products; includes control over gross and fine motor movements and the ability to manipulate external objects.

6. Intrapersonal intelligence - the ability to recognize one's own feelings, intentions and motives.

7. Interpersonal intelligence - the ability to recognize and discriminate between the feelings, attitudes and intentions of other people.

(Adapted from: Gardner, Kornhaber & Wake, 1996)

In particular, Gardner argues that musical intelligence, including the ability to perceive pitch and rhythm, has been more important than logico-mathematical for much of human history. Body-kinesthetic intelligence includes control of one's body and the ability to skillfully manipulate objects: dancers, gymnasts, artisans, and neurosurgeons are examples. Personal intelligence consists of two parts. Intrapersonal intelligence is the ability to monitor one's feelings and emotions, distinguish between them, and use this information to guide one's actions. Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to notice and understand the needs and intentions of others and monitor their mood in order to predict their future behavior.

Gardner analyzes each type of intelligence from several positions: the cognitive operations involved in it; the appearance of child prodigies and other exceptional personalities; data on cases of brain damage; its manifestations in different cultures and possible course evolutionary development. For example, with certain brain damage, one type of intelligence may be impaired, while others remain unaffected. Gardner notes that the abilities of adult representatives of different cultures are different combinations of certain types of intelligence. Although all normal individuals are capable of exhibiting all varieties of intelligence to some degree, each individual has a unique combination of more and less developed intellectual abilities (Walters & Gardner, 1985), which explains the individual differences between people.

As we have noted, conventional IQ tests are good predictors of college grades, but they are less valid in predicting future job success or career advancement. Measures of other abilities, such as personal intelligence, may help explain why some excellent college performers become miserable failures later in life, while less successful students become worship leaders (Kornhaber, Krechevsky & Gardner, 1990). Therefore, Gardner and his colleagues call for an "intellectual-objective" assessment of students' abilities. This will allow children to demonstrate their abilities in ways other than paper tests, such as putting together different elements to demonstrate spatial imagination skills.

Anderson's Theory of Intelligence and Cognitive Development

One of the criticisms of Gardner's theory indicates that a high level of ability related to any of the manifestations of intelligence he identifies, as a rule, correlates with a high level of ability related to other manifestations of intelligence; that is, that none of the specific abilities are completely independent of the others (Messick, 1992; Scarr, 1985). In addition, psychologist Mike Anderson points out that Gardner does not clearly define the nature of multiple intellectual abilities - he calls them "behaviors, cognitive processes, brain structures" (1992, p. 67). Because of this uncertainty, Anderson tried to develop a theory based on the idea of general intelligence put forward by Thurstone and others.

Anderson's theory states that individual differences in intelligence and developmental changes in the level of intellectual competence are explained by a number of various mechanisms. Differences in intelligence are the result of differences in the "basic information processing mechanisms" that involve thinking and, in turn, lead to the acquisition of knowledge. The speed at which recycling processes proceed varies from individual to individual. Thus, an individual with a slow functioning basic processing mechanism is likely to have greater difficulty in acquiring new knowledge than an individual with a fast functioning processing mechanism. This is equivalent to saying that a slow processing mechanism is the cause of a low level of general intelligence.

However, Anderson notes that there are cognitive mechanisms that are not characterized by individual differences. For example, individuals with Down syndrome may not be able to put two and two together, but they are aware that other people have beliefs and act on those beliefs (Anderson, 1992). The mechanisms that provide such universal abilities are called "modules". Each module functions independently, performing complex calculations. Modules are not affected by the underlying processing mechanisms; in principle, they are automatic. According to Anderson, it is the maturation of new modules that explains the growth of cognitive abilities in the process of individual development. For example, the maturation of the module responsible for speech explains the development of the ability to speak in full (expanded) sentences.

According to Anderson's theory, in addition to modules, intelligence includes two "specific abilities". One of them is related to propositional thinking (a linguistic mathematical expression), and the other is related to visual and spatial functioning. Anderson believes that tasks that require these abilities are performed by "specific processors". Unlike modules, specific processors are affected by underlying processing mechanisms. High-speed processing mechanisms allow an individual to use specific processors more efficiently and thereby score higher on tests and achieve more in real life.

Thus, Anderson's theory of intelligence suggests that there are two different "routes" to the acquisition of knowledge. The first involves the use of basic processing mechanisms, leading through specific processors to the acquisition of knowledge. From Anderson's point of view, it is this process that we understand by "thinking" and it is he who is responsible for individual differences regarding intelligence (from his point of view, equivalent to differences in knowledge). The second route involves using modules to acquire knowledge. Knowledge based on modules, such as the perception of three-dimensional space, comes automatically if the corresponding module is sufficiently matured, and this explains the development of the intellect.

Anderson's theory can be illustrated by the example of a 21-year-old young man, known by the initials M.A., who suffered from childhood convulsions and was diagnosed with autism. Upon reaching adulthood, he could not speak and received the lowest scores on psychometric tests. However, he was found to have an IQ of 128 and an extraordinary ability to operate. prime numbers, which he performed more accurately than a specialist who has degree in mathematics (Anderson, 1992). Anderson concluded that M.A.'s basic processing mechanism was not damaged, which allowed him to think in abstract symbols, but his linguistic modules were affected, which prevented him from mastering everyday knowledge and communication processes.

Sternberg's triarchic theory

Unlike Anderson's theory, Sternberg's triarchic theory considers individual experience and context, as well as the basic mechanisms of information processing. Sternberg's theory includes three parts, or sub-theories: a component sub-theory that considers thought processes; experimental (experiential) sub-theory, which considers the influence of individual experience on intelligence; a contextual sub-theory that considers environmental and cultural influences (Sternberg, 1988). The most developed of them is the component subtheory.

Component theory considers the components of thinking. Sternberg identifies three types of components:

1. Metacomponents used for planning, control, monitoring and evaluation of information processing in the process of solving problems.

2. Executive components responsible for the use of problem solving strategies.

3. Components of knowledge acquisition (knowledge), responsible for coding, combining and comparing information in the process of solving problems.

These components are interconnected; they all participate in the process of solving the problem, and none of them can function independently of the others.

Sternberg considers the functioning of the components of intelligence on the example of the following analogy task:

“A lawyer treats a client as a doctor treats: a) medicine; b) patient"

A series of experiments with such problems led Sternberg to conclude that the encoding process and the comparison process are critical components. The subject encodes each of the words of the proposed task by forming a mental representation of this word, in this case, a list of features of this word, reproduced from long-term memory. For example, a mental representation of the word "lawyer" might include the following attributes: college education, knowledge of legal procedures, representing a client in court, and so on. After the subject has formed a mental representation for each word from the presented problem, the comparison process scans these representations for matching features that lead to a solution to the problem.

Other processes are also involved in analogy problems, but Sternberg showed that individual differences in the solutions to this problem fundamentally depend on the efficiency of the coding and comparison processes. According to experimental data, individuals who perform better in solving analogy problems (experienced in solving) spend more time coding and form more accurate mental representations than individuals who perform poorly in such tasks (inexperienced in solving). At the comparison stage, on the contrary, those who are experienced in solving compare features faster than those who are inexperienced, but both are equally accurate. Thus, the better performance of proficient subjects is based on the greater accuracy of their encoding process, but the time it takes them to solve a problem is a complex mixture of slow encoding and fast comparison (Galotti, 1989; Pellegrino, 1985).

However, it is not possible to fully explain the individual differences between people observed in the intellectual sphere with the help of the component subtheory alone. To explain the role of individual experience in the functioning of the intellect, a experimental theory. According to Sternberg, differences in people's experiences affect the ability to solve specific problems. An individual who has not previously encountered a particular concept, such as a mathematical formula or analogy problems, will have more difficulty using this concept than an individual who has already had a chance to use it. Thus, individual experience associated with a particular task or problem can range from complete lack of experience to automatic completion of the task (that is, to complete familiarity with the task as a result of long-term experience with it).

Of course, the fact that an individual is familiar with certain concepts is largely determined by the environment. This is where contextual sub-theory comes into play. This subtheory considers the cognitive activity required to adapt to specific environmental contexts (Sternberg, 1985). It is focused on the analysis of three intellectual processes: adaptation, selection and formation of the environmental conditions that actually surround him. According to Sternberg, the individual first of all looks for ways to adapt or adapt to the environment. If adaptation is not possible, the individual tries to choose a different environment or to shape the conditions of the existing environment in such a way that he can more successfully adapt to them. For example, if a person is unhappy in a marriage, it may be impossible for him to adapt to his surroundings. Therefore, he or she may choose a different environment (for example, if he or she separates or divorces his or her spouse) or tries to shape existing conditions in a more acceptable way (for example, by going to family counseling) (Sternberg, 1985).

Bioecological theory of Cesi

Some critics argue that Sternberg's theory is so multi-component that its individual parts do not agree with each other (Richardson, 1986). Others point out that this theory does not explain how problem solving is carried out in everyday contexts. Still others point out that this theory largely ignores the biological aspects of intelligence. Stefan Ceci (1990) tried to answer these questions by developing Sternberg's theory and paying much more attention to the context and its influence on the process of problem solving.

Cesi believes that there are "multiple cognitive potentials", as opposed to a single basic intellectual ability or factor of general intelligence g. These multiple abilities or areas of intelligence are biologically determined and impose restrictions on mental (mental) processes. Moreover, they are closely related to the problems and opportunities inherent in the individual environment or context.

According to Cesi, context plays a central role in demonstrating cognitive abilities. By "context" he means areas of knowledge, as well as factors such as personality traits, level of motivation and education. The context can be mental, social and physical (Ceci & Roazzi, 1994). A particular individual or population may lack certain mental abilities, but in the presence of a more interesting and stimulating context, the same individual or population may demonstrate a higher level of intellectual functioning. Let's take just one example; in a well-known longitudinal study of children with high IQ by Lewis Terman (Terman & Oden, 1959), it was suggested that high IQ correlated with high levels of achievement. However, upon closer analysis of the results, it was found that children from wealthy families achieved greater success in adulthood than children from low-income families. In addition, those who grew up during the Great Depression achieved less in life than those who came of age later, at a time when career prospects were greater. As Cesi puts it, "as a result ... the ecological niche that an individual occupies, including factors such as individual and historical development, turns out to be a much more significant determinant of professional and economic success than IQ" (1990, p. 62).

Cesi also argues against the traditional view of the relationship between intelligence and the ability to think abstractly, regardless of the subject area. He believes that the ability for complex mental activity is associated with knowledge acquired in certain contexts or areas. Highly intelligent individuals are not endowed with great abilities for abstract thinking, but have sufficient knowledge in specific areas, allowing them to think in a more complex way about problems in this field of knowledge (Ceci, 1990). In the process of working in a certain field of knowledge - for example, in computer programming - the individual knowledge base grows and becomes better organized. Over time, this allows the individual to improve his intellectual functioning - for example, to develop better computer programs.

Thus, according to Cexi's theory, everyday, or "life", intellectual functioning cannot be explained on the basis of IQ alone or some biological concept of general intelligence. Instead, intelligence is defined by the interaction between multiple cognitive potentials and a vast, well-organized knowledge base.

Theories of Intelligence: Summary

The four theories of intelligence discussed in this section differ in several respects. Gardner attempts to explain the wide variety of adult roles found in different cultures. He believes that such diversity cannot be explained by the existence of a basic universal intellectual ability, and suggests that there are at least seven different manifestations of intelligence, present in various combinations in each individual. According to Gardner, intelligence is the ability to solve problems or create products that have value in a particular culture. According to this view, a Polynesian navigator with developed skills in navigating the stars, a figure skater who successfully performs a triple “Axel”, or a charismatic leader who draws crowds of followers along with him are no less “intellectual” than a scientist, mathematician or engineer.

Anderson's theory attempts to explain various aspects of intelligence - not only individual differences, but also the growth of cognitive abilities in the course of individual development, as well as the existence of specific abilities, or universal abilities that do not differ from one individual to another, such as the ability to see objects in three measurements. To explain these aspects of intelligence, Anderson suggests the existence of a basic processing mechanism equivalent to Spearman's general intelligence, or g factor, along with specific processors responsible for propositional thinking and visual and spatial functioning. The existence of universal abilities is explained using the concept of "modules", the functioning of which is determined by the degree of maturation.

Sternberg's triarchic theory is based on the view that earlier theories of intelligence are not wrong, but only incomplete. This theory consists of three sub-theories: a component sub-theory that considers the mechanisms of information processing; experimental (experiential) sub-theory, which takes into account individual experience in solving problems or being in certain situations; contextual sub-theory that considers the relationship between the external environment and individual intelligence.

Cesi's bioecological theory is a development of Sternberg's theory and explores the role of context at a deeper level. Rejecting the idea of a single general intellectual ability to solve abstract problems, Cesi believes that the basis of intelligence is multiple cognitive potentials. These potentials are biologically determined, but the degree of their manifestation is determined by the knowledge accumulated by the individual in a certain area. Thus, according to Cesi, knowledge is one of the most important factors of intelligence.

Despite these differences, all theories of intelligence have a number of common features. All of them try to take into account the biological basis of intelligence, whether it be a basic processing mechanism or a set of multiple intellectual abilities, modules or cognitive potentials. In addition, three of these theories emphasize the role of the context in which the individual functions, that is, environmental factors that influence intelligence. Thus, the development of a theory of intelligence suggests further study of the complex interactions between biological and environmental factors that are at the center of modern psychological research.

1. Representatives of the behavioral sciences, as a rule, quantify the degree of difference of one group of people from another based on a certain measure of personal quality or ability, calculating the variance of the obtained indicators. The more individuals in a group differ from each other, the higher the variance. Researchers can then determine how much of that variance is attributable to one cause or another. The proportion of the variance of a trait that is explained (or caused) by the genetic difference of individuals is called the heritability of that trait. Since heritability is a proportion, it is expressed as a number from 0 to 1. For example, the heritability of height is about 0.90: differences in people's height are almost entirely due to their genetic differences.

2. Heritability can be assessed by comparing correlations obtained for pairs of identical twins (who share all the genes) and correlations obtained for pairs of related twins (who, on average, share about half of the genes). If, for some trait, pairs of identical twins are more similar than pairs of related ones, then this trait has a genetic component. Heritability can also be assessed by correlation within identical pairs of twins raised apart from each other in different environments. Any correlation within such pairs must be explained by their genetic similarity.

3. Heritability is often misunderstood; therefore, it must be taken into account that: a) it indicates the difference between individuals. It does not show how much of a particular trait in an individual is due to genetic factors; b) it is not a fixed attribute of a feature. If something affects the variability of a trait in a group, then heritability also changes; c) heritability shows the variance in a group. It indicates the source of the mean difference between groups; d) heritability shows how changes in the environment can change average trait in the population.

4. Genetic and environmental factors do not act independently in the formation of personality, but are closely intertwined from the moment of birth. Because both a child's personality and home environments are a function of parental genes, there is a built-in correlation between a child's genotype (inherited personality traits) and that environment.

5. The three dynamic processes of interaction between the individual and the environment include: a) reactive interaction: different individuals experience and interpret the action of the same environment in different ways and react to it differently; b) evoked interaction: the personality of the individual causes different reactions in other people; c) proactive interaction: individuals choose and create their own environment. As the child grows, the role of proactive interaction increases.

6. A number of mysteries have been revealed in twin studies: the heritability estimated from identical twins raised apart is significantly higher than that estimated from comparing identical and consanguineous twins. Identical twins who grew up apart are just as similar to each other as twins who grew up together, but the similarity of related twins and single siblings decreases over time, even if they grew up together. This is partly due, apparently, to the fact that when all the genes are shared, they are more than twice as efficient as when only half of the genes are shared. These patterns can also be partially explained by the three processes of interaction between the person and the environment (reactive, evoked and proactive).

7. Except for genetic similarity, children from the same family are no more similar than children randomly selected from the group. This means that the variables that are usually studied by psychologists (the characteristics of upbringing and the socioeconomic situation of the family) hardly contribute to interindividual differences. Researchers should take a closer look at the differences in children within the same family. This result can also be partially explained by the three processes of interaction between the person and the environment.

8. Tests designed to assess intelligence and personality are required to give repeatable and consistent results (reliability) and measure exactly what they are designed to measure (validity).

9. The first intelligence tests were developed by the French psychologist Alfred Binet, who proposed the concept of mental age. In a gifted child, mental age is above chronological, and in a child with delayed development, it is below chronological. The concept of intelligence quotient (IQ) as the ratio of mental age to chronological age, multiplied by 100, was introduced when the Binet scales were revised and the Stanford-Binet test was created. Many intelligence test scores are still expressed as IQ scores, but they are no longer calculated using the old formula.

10. Both Binet and Wexler, the developer of the Wexler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), believed that intelligence is the general ability to think. Similarly, Spearman suggested that the general intelligence factor (g) determines an individual's performance in relation to various test items. The method of identifying the various abilities underlying achievement on intelligence tests is called factor analysis.

11. In order to identify a comprehensive but reasonable number of personality traits on which to evaluate an individual, the researchers first selected from the complete dictionary all the words (about 18,000) denoting personality traits; then their number was reduced. Individuals' scores on the traits anchored in the remaining terms were processed by factor analysis to determine how many parameters are required to explain the correlations between the scales. Although the number of factors varies from researcher to researcher, scientists recently agreed that a set of five factors would be the best compromise. They were called the "big five" and abbreviated as "OCEAN"; the five main factors are: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, compliance, and neuroticism.

12. Personality questionnaires serve to report individuals on their opinions or reactions to certain situations indicated in the question. Responses to subgroups of test items are summarized to obtain scores on different scales or factors of the questionnaire. Most questionnaire items are compiled or selected on the basis of one theory or another, but they can also be selected by correlation with an external criterion - this method of compiling a test is called criterion binding. The best example available is the Minnesota Multidisciplinary Personality Inventory (MMPI), which was developed to identify individuals with mental disorders. For example, an item to which schizophrenics are significantly more likely than normal people to answer "true" is chosen as the item on the schizophrenia scale.

13. The informational approach to intelligence seeks to explain intellectual behavior in terms of the cognitive processes involved in an individual's solution of tasks from an intelligence test.

14. Recent theories of intelligence include Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences, Anderson's theory of intelligence and cognitive development, Sternberg's triarchic theory, and Cesi's ecobiological theory. All of these theories, to varying degrees, consider the interaction between biological and environmental factors that affect the functioning of the intellect.

Key terms

Heredity

Reliability

Validity

Intelligence quotient (IQ)

Personality

Personality Questionnaire

Questions for reflection

1. If you have siblings, how different are you from them? Can you identify how these differences might be influenced by the person-environment interactions described in this chapter? Can you tell how the parenting strategies used by your parents differed for each of the children in your family, depending on their personality characteristics?

2. Standardized tests such as the SAT provide a nationwide measure of achievement, allowing graduates from any school in the country to compete equally for admission to top colleges. Prior to the introduction of standardized tests, students were often unable to demonstrate that they had the required level of achievement, and colleges favored students from well-known schools or those with "family ties." However, critics argue that the widespread popularity of standardized tests in selecting well-prepared students has led to admissions committees have begun to place too much weight on test scores, and schools have begun to tweak their learning programs for the tests themselves. In addition, critics claim that standardized tests are biased towards certain ethnic groups. Considering all these factors, do you think that the widespread use of standardized tests contributes to or hinders the achievement of the goal of equal opportunity for our society?

3. How would you rate yourself on the Big Five scales that measure personality traits? Do you think that your personality can be adequately described using this model? What aspects of your personality might be overlooked in this description? If you and a close friend (family member) had to describe your personality, what characteristics would you likely disagree on? Why? When describing what traits of your personality could your chosen person be more accurate than yourself? If there are such traits, why can another person describe you more accurately than yourself?

Theories of intelligence.

Conventionally, all factor models of intelligence can be divided into four main groups according to two bipolar features: 1) what is the source of the model - speculation or empirical data, 2) how the intelligence model is built - from individual properties to the whole or from the whole to individual properties (Table 2)

The model can be built on some a priori theoretical assumptions, and then verified (verified) in an empirical study. A typical example of this kind is Guilford's model of intelligence.

More often the author spends a voluminous pilot study, and then theoretically interprets its results, as do numerous authors of tests of the structure of intelligence. This does not exclude the author's ideas that precede empirical work. Ch. Spearman's model can serve as an example.

Typical variants of a multidimensional model, in which many primary intellectual factors are assumed, are the models of the same J. Gilford (a priori), L. Thurstone (a posteriori) and, from domestic authors, V. D. Shadrikov (a priori). These models can be called spatial, single-level, since each factor can be interpreted as one of the independent dimensions of the factor space.

Finally, hierarchical models (C. Spearman, F. Vernon, P. Humphreys) are multilevel. Factors are placed at different levels of generality: at the top level - the factor of general mental energy, at the second level - its derivatives, etc. The factors are interdependent: the level of development of the general factor is associated with the level of development of particular factors.

table 2

Classification of factor models of intelligence

CH. SPEERMAN'S MODEL

C. Spearman dealt with the problems of professional abilities (mathematical, literary and others). When processing test data, he found that the results of many tests aimed at diagnosing the features of thinking, memory, attention, perception are closely related: as a rule, people who successfully perform tests for thinking also successfully cope with tests for other cognitive abilities. and vice versa, low-performing subjects perform poorly on most tests. Spearman suggested that the success of any intellectual work is determined by: 1) a certain general factor, a general ability, 2) a factor specific to this activity. Consequently, when performing tests, the success of the solution depends on the level of development of the testee's general ability (general G-factor) and the corresponding special ability (S-factor). Ch. Spearman used a political metaphor in his reasoning. He represented many abilities as many people - members of society. In a society of abilities, anarchy can reign - abilities are not connected in any way and are not coordinated with each other. An "oligarchy" can dominate - the success of an activity is determined by several basic abilities (as Spearman's opponent, L. Thurstone, later believed). Finally, in the realm of abilities, the “monarch” can rule - the G-factor, to which the S-factors are subordinate.

Spearman, explaining the correlation of the results of various measuring procedures by the influence common property, proposed in 1927 a method of factor analysis of intercorrelation matrices to identify this latent general factor. The G-factor is defined as the total “mental energy” that people are equally endowed with, but which, to one degree or another, affects the success of each specific activity.

Studies of the ratio of general and specific factors in solving various problems allowed Spearman to establish that the role of the G-factor is maximum when solving complex mathematical problems and tasks on conceptual thinking and is minimal when performing sensorimotor actions.

A number of important consequences follow from Spearman's theory. Firstly, the only thing that unites the success of solving a wide variety of tests is the factor of general mental energy. Secondly, the correlations of the results of performance by any group of people of any intellectual tests must be positive. Thirdly, to test the “G” factor, it is best to use tasks to identify abstract relationships.

Further development of the two-factor theory in the works of C. Spearman led to the creation of a hierarchical model: in addition to the factors "G" and "S", he singled out the criterion level of mechanical, arithmetic and linguistic (verbal) abilities. These abilities (Spearman called them "group factors of intelligence") occupied an intermediate position in the hierarchy of factors of intelligence in terms of their level of generalization.

GROUP FACTORS

S-FACTORS

Rice. 1. Spearman model

Subsequently, many authors have tried to interpret the G-factor in traditional psychological terms. A mental process manifesting itself in any kind of mental activity could claim the role of a general factor: attention (Cyril Barth's hypothesis) and motivation were the main contenders. G. Eysenck interprets the G-factor as the speed of information processing by the central nervous system. He established extremely high positive correlations between IQ, determined by high-speed intelligence tests (in particular, tests by G. Eysenck himself), temporal parameters and variability of evoked potentials of the brain, as well as the minimum time that a person needs to recognize a simple image (with tachistoscope presentation) . However, the hypothesis of "speed of information processing by the brain" does not yet have serious neurophysiological arguments.

In addition to the Eysenck tests, other tests are also used to measure the G factor, in particular the Progressive Matrices proposed by J. Raven in 1936, as well as R. Cattell's intelligence tests.

L. THURSTONE MODEL

In the works of Ch. Spearman's opponents, the existence of a common basis for intellectual actions was denied. They believed that a certain intellectual act is the result of the interaction of many individual factors. The main propagandist of this point of view was L. Thurstone, who proposed a method of multivariate analysis of correlation matrices. This method allows you to identify several independent "latent" factors that determine the relationship between the results of performing various tests by a particular group of subjects.

Initially, Thurstone identified 12 factors, of which 7 were most frequently reproduced in studies:

V. Verbal comprehension - is tested by tasks for understanding the text, verbal analogies, conceptual thinking, interpretation of proverbs, etc.

W. Verbal fluency - measured by tests for finding rhymes, naming words belonging to a certain category.

N. Numeric factor - tested by tasks for the speed and accuracy of arithmetic calculations.

S. Spatial factor - divided into two sub-factors. The first determines the success and speed of perception of spatial relationships (recognition of flat geometric shapes). The second is related to the mental manipulation of visual representations in three-dimensional space.

M. Associative memory - measured by tests for the rote memorization of verbal associative pairs.

R. Speed of perception - is determined by the rapid and accurate perception of details, similarities and differences in images. Separate the verbal ("perception of the clerk") and "imaginative" subfactors.

I. Inductive factor - tested by tasks for finding a rule and completing a sequence (by the type of D. Raven's test).

The factors discovered by Thurstone, as shown by the data of further studies, turned out to be dependent (non-orthogonal) "Primary mental abilities" are positively correlated with each other, which speaks in favor of the existence of a single G-factor.

Based on the multifactorial theory of intelligence and its modifications, numerous tests of the structure of abilities have been developed. The most common include the General Aptitude Test Battery (GABT), the Amthauer Intelligence Structure Test (Amthauer Intelligenz-Struktur-Test, I-S-T) and a number of others.

MODEL J. GUILFORD