Arachnids: structure, physiology and development

The arachnid class unites over 36,000 species of terrestrial chelicerae belonging to more than 10 orders.

Arachnida- higher chelicerate arthropods with 6 pairs of cephalothoracic limbs. They breathe through the lungs or trachea and, in addition to the coxal glands, have an excretory apparatus in the form of Malpighian vessels lying in the abdomen.

Structure and physiology. external morphology. The body of arachnids most often consists of a cephalothorax and abdomen. The acron and 7 segments are involved in the formation of the cephalothorax (the 7th segment is underdeveloped). In Solpugs and some other lower forms, only the segments of the 4 front pairs of limbs are soldered together, while the posterior 2 segments of the cephalothorax are free, followed by clearly demarcated segments of the abdomen. Thus, the salpugs have: the anterior part of the body, according to the segmental composition corresponding to the head of trilobites (acron + 4 segments), the so-called propeltidia; two free thoracic segments with legs and a segmented abdomen. Salpugs, therefore, belong to the arachnids with the most richly dissected body.

The next most dismembered detachment is scorpions, in which the cephalothorax is fused, but it is followed by a long 12-segment, like in Gigantostraca, the abdomen, subdivided into a wider anterior abdomen (of 7 segments) and a narrow posterior abdomen (of 5 segments). The body ends in a telson carrying a twisted poisonous needle. This is the same character of segmentation (only without dividing the abdomen into two sections) in representatives of the orders of flagellates, pseudo-scorpions, haymakers, in some ticks and in primitive arthropod spiders.

The next stage of fusion of the trunk segments is found by most spiders and some mites. They have not only the cephalothorax, but also the abdomen, which are continuous undivided parts of the body, but the spiders have a short and narrow stalk between them, formed by the 7th segment of the body. The maximum degree of fusion of body segments is observed in a number of representatives of the order of ticks, in which the whole body is whole, without borders between segments and without constrictions.

As already mentioned, the cephalothorax carries 6 pairs of limbs. The two front pairs are involved in the capture and crushing of food - these are chelicerae and pedipalps. Chelicerae are located in front of the mouth, most often in arachnids they are in the form of short claws (solpugs, scorpions, false scorpions, haymakers, some ticks, etc.). They usually consist of three segments, the terminal segment plays the role of a movable claw finger. More rarely, chelicerae end in a movable claw-like segment or have the appearance of two-segmented appendages with a pointed and serrated edge, with which ticks pierce the integument of animals.

The limbs of the second pair, pedipalps, consist of several segments. With the help of a chewing outgrowth on the main segment of the pedipalp, food is crushed and kneaded, while the other segments make up the genus of tentacles. In representatives of some orders (scorpions, false scorpions), pedipalps are turned into powerful long claws, in others they look like walking legs. The remaining 4 pairs of cephalothoracic limbs consist of 6-7 segments and play the role of walking legs. They end in claws.

In adult arachnids, the abdomen is devoid of typical limbs, although they undoubtedly descended from ancestors with well-developed legs on the anterior abdominal segments. In the embryos of many arachnids (scorpions, spiders), the rudiments of legs are laid on the abdomen, which only subsequently undergo regression. However, in the adult state, the abdominal legs are sometimes preserved, but in a modified form. So, in scorpions on the first segment of the abdomen there is a pair of genital opercula, under which the genital opening opens, on the second - a pair of comb organs, which are equipped with numerous nerve endings and play the role of tactile appendages. Both those and others represent modified limbs. The nature of the lung sacs located on the segments of the abdomen in scorpions, some spiders and pseudoscorpions is the same.

Spider web warts also originate from the limbs. On the lower surface of the abdomen in front of the powder, they have 2-3 pairs of tubercles, seated with hairs and carrying tube-like ducts of numerous arachnoid glands. The homology of these arachnoid warts to the abdominal limbs is proved not only by their embryonic development, but also by their structure in some tropical spiders, in which the warts are especially strongly developed, consist of several segments and even resemble legs in appearance.

Integuments of chelicerae They consist of the cuticle and the underlying layers: the hypodermal epithelium (hypoderm) and the basement membrane. The cuticle itself is a complex three-layer formation. Outside, there is a lipoprotein layer, which reliably protects the body from moisture loss during evaporation. This allowed the chelicerae to become a real land group and populate the most arid regions of the globe. The strength of the cuticle is given by proteins, tanned with phenols and encrusting chitin.

Derivatives of the skin epithelium are some glandular formations, including poisonous and spider glands. The first are characteristic of spiders, flagellates and scorpions; the second - to spiders, false scorpions and some ticks.

Digestive system in representatives of different orders of chelicerates varies greatly. The foregut usually forms an extension - a pharynx equipped with strong muscles, which serves as a pump that draws in semi-liquid food, since arachnids do not take solid food in pieces. A pair of small "salivary glands" open into the foregut. In spiders, the secretion of these glands and the liver is able to break down proteins vigorously. It is introduced into the body of the killed prey and brings its contents into a state of liquid slurry, which is then absorbed by the spider. This is where the so-called extraintestinal digestion takes place.

In most arachnids, the midgut forms long lateral protrusions that increase the capacity and absorptive surface of the intestine. So, in spiders, 5 pairs of blind glandular sacs go from the cephalothoracic part of the middle intestine to the bases of the limbs; similar protrusions are found in ticks, harvestmen and other arachnids. In the abdominal part of the middle intestine, the ducts of the paired digestive gland - the liver - open; it secretes digestive enzymes and serves to absorb nutrients. Intracellular digestion takes place in the liver cells.

excretory system arachnids compared to horseshoe crabs has a completely different character. At the border between the middle and hindgut, a pair of mostly branching Malpighian vessels opens into the alimentary canal. Unlike Tracheata they are of endodermal origin, that is, they are formed at the expense of the midgut. Both in the cells and in the lumen of the Malpighian vessels there are numerous grains of guanine, the main excretory product of arachnids. Guanine, like uric acid excreted by insects, has low solubility and is removed from the body in the form of crystals. At the same time, moisture loss is minimal, which is important for animals that have switched to life on land.

In addition to the Malpighian vessels, arachnids also have typical coxal glands - paired sac-like formations of mesodermal nature, lying in two (rarely in one) segments of the cephalothorax. They are well developed in embryos and at a young age, but in adult animals they more or less atrophy. Fully formed coxal glands consist of a terminal epithelial sac, a looped convoluted canal, and a more direct excretory duct with a bladder and external opening. The terminal sac corresponds to the ciliated funnel of the coelomoduct, the opening of which is closed by the remainder of the coelomic epithelium. The coxal glands open at the base of the 3rd or 5th pair of limbs.

Nervous systemArachnida varied. Being connected in origin with the ventral nerve chain of annelids, in arachnids it shows a pronounced tendency to concentration.

The brain has a complex structure. It consists of two sections: the anterior, which innervates the eyes, is the protocerebrum and the posterior is the tritocerebrum, which sends nerves to the first pair of limbs - the chelicerae. The intermediate part of the brain, the deutocerebrum, characteristic of other arthropods (crustaceans, insects), is absent in arachnids. This is due to the disappearance in them, like in the rest of the chelicerae, of the appendages of the acron - antennules, or antennae, which are innervated precisely from the deutocerebrum.

The metamerism of the ventral nerve cord is preserved most clearly in scorpions. They have, in addition to the brain and peripharyngeal connectives, a large ganglionic mass in the cephalothorax on the ventral side, giving nerves to the 2nd-6th pairs of limbs and 7 ganglia, throughout the abdominal part of the nerve chain. In salpugs, in addition to the complex cephalothoracic ganglion, one more node remains on the nerve chain, and in spiders, the entire chain has already merged into the cephalothoracic ganglion.

Finally, in harvestmen and ticks there is not even a clear distinction between the brain and the cephalothoracic ganglion, so that the nervous system forms a continuous ganglionic ring around the esophagus.

sense organsArachnida varied. Mechanical, tactile stimuli, which are very important for arachnids, are perceived by differently arranged sensory hairs, which are especially numerous on the pedipalps. Special hairs - trichobothria, located on the pedipalps, legs and surface of the body, register air vibrations. The so-called lyre-shaped organs, which are small gaps in the cuticle, to the membranous bottom of which sensitive processes of nerve cells fit, are organs of chemical sense and serve for smell. The organs of vision are represented by simple eyes, which most arachnids have. They are located on the dorsal surface of the cephalothorax and usually there are several of them: 12, 8, 6, less often 2. Scorpions, for example, have a pair of median larger eyes and 2-5 pairs of lateral ones. Spiders most often have 8 eyes, usually arranged in two arcs, with the middle eyes of the anterior arc being larger than the others.

Scorpions recognize their own kind only at a distance of 2-3 cm, and some spiders - for 20-30 cm. In jumping spiders (family. Salticidae) vision plays a particularly important role: if males cover their eyes with opaque asphalt varnish, then they cease to distinguish between females and produce the "love dance" characteristic of the mating period.

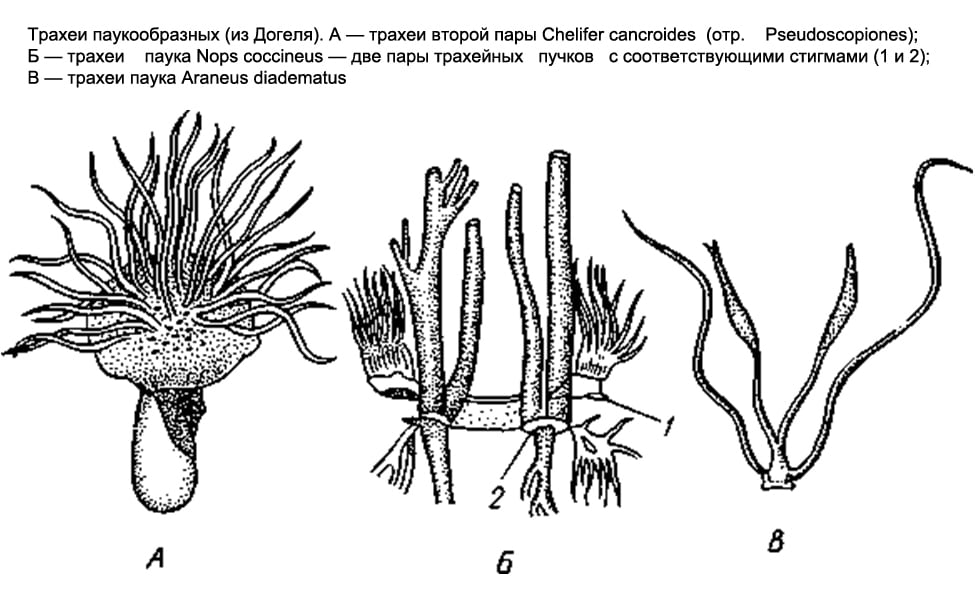

Respiratory system Arachnids are varied. Some have lung sacs, others have tracheae, and others have both at the same time.

Only lung sacs are found in scorpions, flagellates, and primitive spiders. In scorpions, on the abdominal surface of the 3rd-6th segments of the anterior abdomen, there are 4 pairs of narrow slits - spiracles that lead to the lung sacs. Numerous leaf-like folds parallel to each other protrude into the cavity of the sac, between which narrow slit-like spaces remain, air penetrates into the latter through the respiratory gap, and hemolymph circulates in the lung leaflets. The flagellated and lower spiders have only two pairs of lung sacs.

In most other arachnids (solpugs, haymakers, false scorpions, some ticks), the respiratory organs are represented by tracheae. There are paired respiratory openings, or stigmata, on the 1st or 2nd segments of the abdomen (on the 1st thoracic segment in the salpugs). From each stigma, a bundle of long, thin air tubes of ectodermal origin, blindly closed at the ends, extends into the body (they form as deep protrusions of the outer epithelium). In false scorpions and ticks, these tubes, or tracheas, are simple and do not branch; in haymakers, they form side branches.

Finally, in the order of spiders, both types of respiratory organs are found together. The lower spiders, as already noted, have only lungs; among 2 pairs they are located on the lower side of the abdomen. The rest of the spiders retain only one anterior pair of lungs, and behind the latter there is a pair of tracheal bundles that open outwards with two stigmas. Finally, in one family of spiders ( Caponiidae) there are no lungs at all, and the only respiratory organs are 2 pairs of tracheas.

The lungs and trachea of arachnids arose independently of each other. The lung sacs are undoubtedly more ancient organs. It is believed that the development of the lungs in the process of evolution was associated with a modification of the ventral gill limbs, which the aquatic ancestors of arachnids possessed and which were similar to the gill-bearing ventral legs of horseshoe crabs. Each of these limbs retracted into the body. This created a cavity for the lung leaflets. The lateral edges of the stalk adhered to the body almost along its entire length, except for the area where the respiratory gap was preserved. The abdominal wall of the lung sac, therefore, corresponds to the former limb itself, the anterior section of this wall corresponds to the base of the leg, and the lung leaflets originated from the gill plates located on the back of the abdominal legs of the ancestors. This interpretation is confirmed by the development of lung sacs. The first folded rudiments of the lung plates appear on the posterior wall of the corresponding rudimentary legs before the limb deepens and turns into the lower wall of the lung.

The tracheae arose independently of them and later as organs more adapted to air breathing.

Some small arachnids, including some mites, have no respiratory organs, and breathing takes place through thin covers.

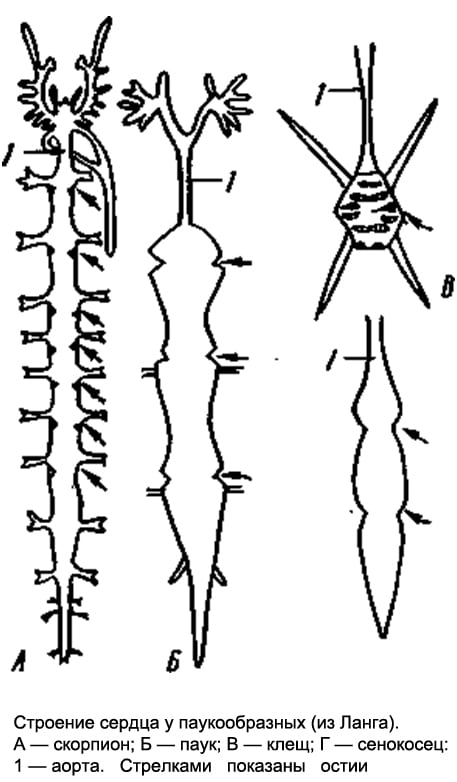

Circulatory system. In forms with pronounced metamerism (scorpions), the heart is a long tube lying in the anterior abdomen above the intestines and equipped with 7 pairs of slit-like awns on the sides. In other arachnids, the structure of the heart is more or less simplified: for example, in spiders it is somewhat shortened and carries only 3-4 pairs of ostia, while in haymakers, the number of the latter is reduced to 2-1 pairs. Finally, in ticks, the heart at best turns into a short pouch with one pair of awns. In most ticks, due to their small size, the heart completely disappears.

From the anterior and posterior ends of the heart (scorpions) or only from the anterior (spiders) departs through the vessel - the anterior and posterior aorta. In addition, in a number of forms, a pair of lateral arteries departs from each chamber of the heart. The terminal branches of the arteries pour out the hemolymph into the system of lacunae, that is, into the spaces between the internal organs, from where it enters the pericardial part of the body cavity, and then through the ostia into the heart. The hemolymph of arachnids contains a respiratory pigment, hemocyanin.

Sexual system. Arachnids have separate sexes. The gonads lie in the abdomen and in the most primitive cases are paired. Very often, however, there is a partial fusion of the right and left gonads. Sometimes, in one sex, the gonads are still paired, while in the other, the fusion has already occurred. So, male scorpions have two testes (each of two tubes connected by jumpers), and females have one whole ovary, consisting of three longitudinal tubes connected by transverse adhesions. In spiders, in some cases, the gonads remain separate in both sexes, while in others, in the female, the posterior ends of the ovaries grow together, and a whole gonad is obtained. Paired genital ducts always depart from the gonads, which merge together at the anterior end of the abdomen and open outward through the genital opening, the latter in all arachnids lies on the first segment of the abdomen. Males have various additional glands, females often develop spermatheca.

Development. Instead of external fertilization, which was characteristic of the distant aquatic ancestors of arachnids, they developed internal fertilization, accompanied in primitive cases by spermatophoric insemination or, in more advanced forms, by copulation. The spermatophore is a sac secreted by the male, which contains a portion of seminal fluid, thus protected from drying out during exposure to air. In false scorpions and in many ticks, the male leaves the spermatophore on the ground, and the female captures it with the external genitalia. At the same time, both individuals perform a "nuptial dance" consisting of characteristic postures and movements. The males of many arachnids carry the spermatophore into the female genital opening with the help of chelicerae. Finally, some forms have copulatory organs, but no spermatophores. In some cases, parts of the body that are not directly connected with the reproductive system serve for copulation, for example, modified terminal segments of the pedipalps in male spiders.

Most arachnids lay eggs. However, many scorpions, false scorpions, and some ticks have live births. Eggs are mostly large, rich in yolk.

In arachnids, various types of cleavage occur, but in most cases surface cleavage occurs. Later, due to the differentiation of the blastoderm, the germinal streak is formed. Its surface layer is formed by the ectoderm, the deeper layers are the mesoderm, and the deepest layer adjacent to the yolk is the endoderm. The rest of the embryo is dressed only in ectoderm. The formation of the body of the embryo occurs mainly due to the embryonic streak.

In further development, it should be noted that segmentation is more pronounced in embryos, and the body consists of a larger number of segments than in adult animals. So, in the embryos of spiders, the abdomen consists of 12 segments, similar to adult scorpions and scorpions, and there are rudiments of legs on 4-5 anterior segments. With further development, all abdominal segments merge, forming a whole abdomen. In scorpions, the limbs are laid on 6 segments of the anterior abdomen. The anterior pair of them gives genital caps, the second - comb organs, and the development of other pairs is associated with the formation of lungs. All this indicates that the class Arachnida descended from ancestors with rich segmentation and with limbs developed not only on the cephalothorax, but also on the abdomen (prone belly). Almost all arachnids have direct development, but mites have metamorphosis.

Literature: A. Dogel. Zoology of invertebrates. Edition 7, revised and enlarged. Moscow "High School", 1981